گاهی در سینما احساسی که فیلم از خودش بهجا میگذارد از داستان مهم تر است. این احساس است که تبدیل به قهرمان اصلی میشود. احساسی که در فیلم آرام آرام تهی میشود، مثل رنگی که زیر آفتاب میپوسد. سه فیلم از سه دنیای متفاوت ، ۴۰۰ ضربه تروفو، یک اتفاق ساده سهراب شهید ثالث و اسب تورین بلا تار، در ظاهر هیچ ربطی به هم ندارند، اما هر سه دربارهی یک چیز حرف میزنند: فروپاشیِ توانِ احساس کردن.

در این فیلمها، انسان دیگر چیزی را حس نمی کند و تنها ادامه میدهد. حس در آنها مثل نوری است که تدریجاً و در سکوت درون خاموش میشود.

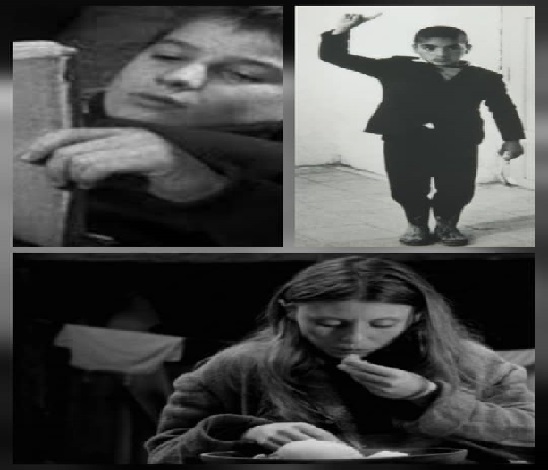

در فیلم تروفو، کودک هنوز میخواهد حس کند. آنتوان میدود، فرار میکند، دلش میخواهد ببیند و لمس کند و بفهمد. دنیای اطرافش پر ریا و دروغگوست، اما او هنوز در برابرش چون قلبی میتپد. این تپش، مقاومتی غریزی در برابر سردی جهان و آغاز شورِ زندگی است.

اما در جهان سهراب شهید ثالث، محمد دیگر حتی برای تپیدن هم رمقی ندارد. او نه اعتراض میکند، نه سؤال دارد، نه امید. زندگی برایش بیهیجان است و نه دردناک. اتفاقها رخ میدهند بیآنکه برای او معنایی داشته باشند. در زندگی محمد سکوتی طولانی روی همهچیز کشیده شده است. در این فیلم، حس هنوز وجود دارد، اما خسته و بیجان، مثل چراغی که شعلهاش به زحمت زنده مانده است.

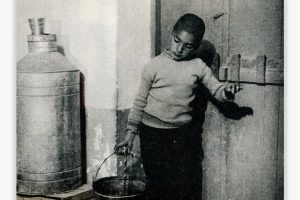

در نهایت، در دنیای بلا تار دیگر هیچچیز برای حس کردن باقی نمانده است. باد میوزد، اسب تورین از حرکت میایستد، آدمها میخورند و میخوابند، و جهان به سوی خاموشی پیش میرود. اینجا حتی خستگی هم نیست، فقط سکون است. گویی احساس، آخرین موجود زندهی زمین بود که حالا مُرده است. بلا تار جهانی را میسازد که در آن فقط دوامِ بیمعنا مانده و از اشتیاق و حتی اندوه خبری نیست.

اگر این سه فیلم را پشت سر هم ببینید، انگار سیر مرگِ احساس را تماشا میکنید.

در ۴۰۰ ضربه، احساس جوان و سرکش است؛ در یک اتفاق ساده، فرسوده و بیرمق؛ و در اسب تورین، مرده است. تروفو هنوز به امکانِ وجود حس ایمان دارد، شهید ثالث در تردید است، و بلا تار از آن گذشته است. این سه، سه فصل از یک تاریخ پنهاناند: زایش، پوسیدگی، و خاموشی.

زبان هم در مسیر همین فرسودگی از بین میرود. در ۴۰۰ ضربه، زبان دروغ میگوید و فریب میدهد؛ در یک اتفاق ساده، زبان از کار افتاده، حرفها نیمهتمام میمانند؛ و در اسب تورین، دیگر کلامی وجود ندارد. هرچه جلوتر میرویم، سکوت پررنگتر میشود، تا جایی که تنها چیزی که میشنویم صدای باد یعنی صدای آخرین بازماندهی حس در جهانی بیاحساس است.

کودک در این میان نقش آینه را دارد. در تروفو، کودک هنوز میتواند جهانی تازه تصور کند، هنوز به دریا فکر میکند. در شهید ثالث، کودک فقط بازتاب بزرگترهاست، تکرارِ بیهیجانِ خستگی آنها و در بلا تار دیگر حتی کودکی وجود ندارد؛ همهچیز در پیری و سکون فرو رفته است. معصومیت، همانطور که جهان پیش میرود، از بین میرود.

این سه فیلم با هم دربارهی از دست رفتنِ معصومیتاند، اما نه به معنای اخلاقیاش، بلکه به معنای از بین رفتن توانِ شگفتزده شدن، توانِ احساس کردن.

سینمای هر سه کارگردان، در عمق، بر پایهی حس ساخته شده، نه داستان. تروفو با جنبوجوش دوربین، حس را زنده میکند؛ شهید ثالث با سکوت و فاصله، آن را تحلیل میبرد؛ و بلا تار با تکرار و تاریکی، آن را میکُشد. سه مسیر برای گفتن یک حقیقت: انسان دیگر نمیتواند حس کند.

وقتی آنتوان در پایان ۴۰۰ ضربه به دریا میرسد، هنوز نوری هست؛ نوری سرد اما زنده. وقتی محمد در یک اتفاق ساده به جای خالی مادر نگاه میکند، نور هنوز هست، ولی دیگر گرما ندارد. در اسب تورین، دیگر هیچ نوری باقی نمانده. تاریکی آخرین صحنه از خودِ جهان است.

شاید هیچکدام از این سه فیلمساز نخواستند با دیگری گفتوگو کنند، اما حالا که در کنار هم قرارشان میدهیم، به زبانی واحد حرف میزنند: داستان مرگِ تدریجیِ احساس در انسان معاصر.

و همین یک جمله، شاید ترسناکترین حقیقتی باشد که سینما تا امروز گفته است.

نویسنده: دکتر لیلی خوش گفتار

The Slow Death of Feeling in the Modern Human

Sometimes in cinema, the emotion a film leaves behind matters more than the story itself. It’s the emotion that becomes the true protagonist — an emotion that slowly drains away, like a color fading under the sun. Three films from three distant worlds — Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, Sohrab Shahid Saless’s A Simple Event, and Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse — seem unrelated on the surface, yet all three speak of the same thing: the collapse of our ability to feel.

In these films, the human being no longer reacts; he simply continues. Feeling becomes a dim light that fades gradually, quietly, from within.

In Truffaut’s film, the child still wants to feel. Antoine runs, escapes, longs to see, to touch, to understand. The world around him is full of lies and hypocrisy, but he still beats against it like a heart that refuses to stop. That heartbeat is a primal resistance to the coldness of the world — the first spark of life’s passion.

In Shahid Saless’s world, Mohammad no longer has the strength even to beat. He neither protests nor questions nor hopes. Life for him is dull rather than painful. Things happen without meaning, and a long silence covers everything. Feeling still exists, but faintly — like a flame barely holding on to life.

And in Béla Tarr’s universe, there is nothing left to feel at all. The wind blows, the horse stops moving, people eat and sleep, and the world slides toward darkness. Even fatigue has vanished; only stillness remains. It’s as if feeling itself was the last living creature on earth — and it has just died. Tarr’s world is one of endurance without purpose, stripped of longing, even of sorrow.

Watching these three films in sequence is like witnessing the gradual death of emotion.

In The 400 Blows, feeling is young and rebellious; in A Simple Event, it’s weary and faint; and in The Turin Horse, it’s gone. Truffaut still believes in the possibility of feeling; Shahid Saless is uncertain; Béla Tarr has moved beyond it. Together, they form three hidden chapters of a single story: birth, decay, and extinction.

Language itself deteriorates along the same path. In The 400 Blows, words deceive; in A Simple Event, speech falters and trails off; and in The Turin Horse, there are no words left at all. The further we go, the louder the silence becomes — until the only thing we hear is the wind, the last survivor of feeling in a senseless world.

The child, in all this, is a mirror.

In Truffaut, the child can still imagine a new world, still dream of the sea. In Shahid Saless, the child merely reflects the weary adults around him. And in Tarr, there are no children left; everything has aged and gone still. Innocence fades, not in a moral sense, but as the loss of our capacity for wonder — the loss of our ability to feel.

Each of these filmmakers builds cinema not on story, but on sensation. Truffaut revives feeling through restless movement; Shahid Saless dissects it through silence and distance; and Tarr kills it through repetition and darkness. Three different routes toward a single truth: humanity can no longer feel.

When Antoine reaches the sea at the end of The 400 Blows, there is still light — cold, but alive.

When Mohammad stares at his mother’s empty bed in A Simple Event, the light remains, but it no longer warms.

And in The Turin Horse, there is no light at all. Darkness isn’t the final scene — it’s the world itself.

Perhaps none of these three filmmakers intended to speak to one another, yet when placed side by side, their voices merge into one: the story of the slow death of feeling in the modern human being.

And perhaps that is the most terrifying truth cinema has ever told.

writer: Dr. Leily Khoshgoftar